2 years after the murder of George Floyd, what has changed?

MINNEAPOLIS (FOX 9) - Like many Minnesotans, Zaynab Mohamed remembers exactly where she was when she saw the video of Derek Chauvin murdering George Floyd.

It was the evening of May 25, 2020, and she was scrolling Facebook when she saw a post with the video shared by local organizer and civil rights lawyer Nekima Levy Armstrong.

"I remember being in bed at like 10 p.m., just kind of going through my phone. And then it came. Nekima had posted this really horrific video. And obviously, I always have known about police shootings … but I remember going to bed and like waking up the next day, and it just felt different."

It was different. The video, captured by Darnella Frazier, who was 17 at the time, sparked the largest protest movement against racism and racial injustice America has seen in a generation and a racial reckoning that reverberated across the world.

Protesters hold signs during demonstrations following the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis. (Photo by Fox 9 Producer Samy Verne)

It would also prove to be a turning point for Mohamed in the same way it would for thousands of others across the city and country.

"I remember looking at it (the video) and sending it to all my friends. I remember posting all over social media and I don't think I've ever done that before. And so then I started going to protests from that day on. That was kind of my start into the movement," she said.

Zaynab Mohamed speaks at a march during protests following the murder of George Floyd in May of 2020.

Two years on, the legacy of the social movement that started in Minneapolis and spread across the country after Floyd’s murder is still being defined. The protests undeniably helped create change, whether you consider how they helped change the conversation around racism, or the impact they had on the case itself (the Walz administration agreed to activists' demands to appoint Keith Ellison to lead the prosecution, who then brought more additional changes against Chauvin and the other three officers, for instance). The protests also led to concrete policy changes, like city, state and federal bans against law enforcement using chokeholds.

But activists across the Twin Cities tend to share a sense of a missed opportunity, while still maintaining hope for the future. The sense of shared urgency about the need for action on racial equity and police reform faded in the months after Chauvin's conviction, and on the policy front, efforts for ambitious, sweeping reforms stalled at city, state and federal levels.

RELATED: 2 years since George Floyd's killing, activists still seek reforms

"Two years later, you expect something to change, but you can't change an entire system within two years. Right? Like that's a reality that we live in," Mohamed said. "But I'm hopeful that people will continue organizing. I'm hopeful that people will continue to speak truth to power and never compromise their values and ensuring that everyone in the state lives in a more equitable world."

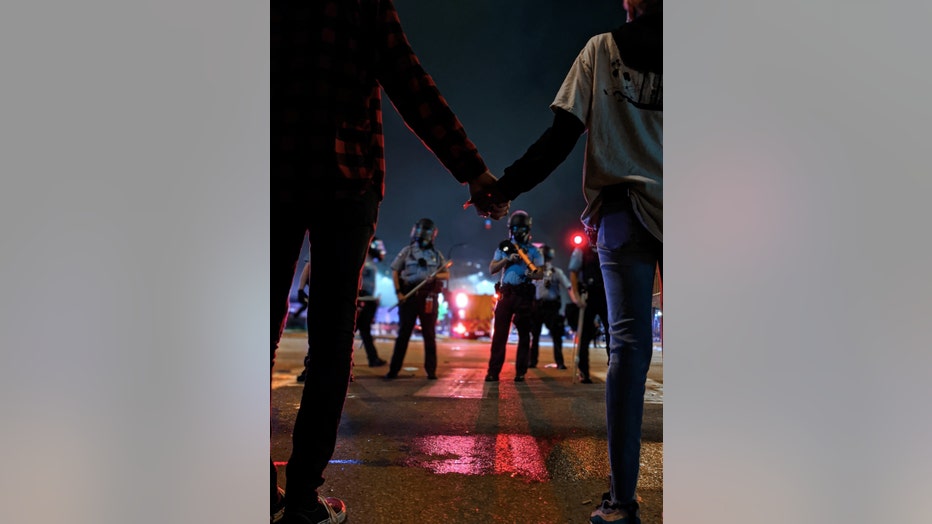

Protesters hold hands as they face a line of police officers during demonstrations following the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis. (Photo by FOX 9 Producer Samy Verne)

Policing on the federal level

Biden to sign policing executive order on Floyd anniversary

On the second anniversary of George Floyd?s death President Joe Biden will sign an executive order to review use of force policies, restrict flow of military surplus equipment and encourage limitations on no-knock warrants.

The George Floyd protests and the social movement they inspired helped mobilize Black voters who, in turn, helped propel Jose Biden to victory over Donald Trump in November 2020.

Biden campaigned on police reform, and after he was elected, many thought a bipartisan compromise would be possible.

But the momentum proved to be fleeting. The president’s signature police reform bill, George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, which aimed to address excessive force and racial bias in policing, passed the House but stalled in the gridlocked Senate. Negotiations dragged on before collapsing in September 2021, with Democrats and Republicans unable to come to an agreement on ending qualified immunity, which would allow police officers to be sued for violating a person’s civil rights, or the creation of a national database to track police misconduct.

The president on Wednesday is expected to take unilateral action by issuing an executive order in Floyd’s name. (We will update this story when the details are announced.)

Police reform in Minnesota

Similarly, police accountability pushed by some DFL lawmakers in the wake of Floyd's death stalled in the state Senate after Republicans said they wouldn’t back any proposals that weren’t supported by law enforcement groups.

Mohamed, who is now the DFL-endorsed candidate for state Senate District 63, was involved in the state push through her position with CAIR Minnesota. She said the compromise measures that did make it through the Legislature, including a ban on chokeholds, were far short of what activists had hoped for, as they lacked accountability measures.

"And then we passed a lot more money for four police departments and less accountability. And what we were hoping for the outcome would be to have accountability. You're going to have law enforcement across the state, but how do you have law enforcement that's accountable to the people?" she said.

Just as Biden is reportedly doing today, Walz took executive action on police reform last June with an order that, among other things, shifted American Rescue Plan funds to violence prevention programs and required state law enforcement agencies to let families of people killed by police see the body cam footage within five days.

Minneapolis police policy changes

Memorialize the Movement displays street art created after George Floyd's murder

The street art created after George Floyd was murdered by Minneapolis police was put on display in Phelps Field Park over the weekend ahead of the second anniversary of Floyd's death. It marked the second exhibition from Memorialize the Movement, which has worked to preserve the plywood boards created in May 2020 and months thereafter.

On June 10, 2020, less than a month after Floyd’s murder, with Minneapolis still reeling, Mayor Jacob Fry did a national TV interview with CBS News on the subject of police reform.

Frey had already made clear he was against abolishing or defunding the police department. A few days before, when activists had confronted him outside his apartment in Northeast Minneapolis and asked if he would defund the police, he had said no, then retreated as the crowd chanted, "Go home, Jacob, go home." But, as he argued in the interview, while he didn’t want to defund the police, he did want to overhaul how the department was run.

RELATED: Minneapolis police, city violated civil rights law, state concludes

"Let me be exceedingly clear, we need deep structural reform to how the police department has done business for years in a way that has failed black and brown people repeatedly. We need a full-on culture shift in terms of the way the police department does business. But am I for abolishing the entire department? No, I’m not," he said

Frey was also clear on what he saw as the principal obstacle to that change.

"The elephant in the room is the police union, the collective bargaining agreement. It's the arbitration provisions that are set up that quite literally prevent the chief and I, in many instances, from both disciplining and terminating officers who have had wrongful conduct. If we're really serious about reform, if we're really serious about changing the game, we need to attack those provisions," he said.

A lot has changed since Frey gave that interview, and a lot hasn’t — including those provisions.

Minneapolis has steadily made changes to its police policies since Floyd’s murder, as detailed in this timeline provided by Frey’s office.

The first set of MPD policy changes following Floyd’s murder came via court order after a state agency intervened. On June 8, 2020, the Minnesota Department of Human Rights obtained a temporary restraining order against the city mandating a series of changes to MPD policy.

These included a ban on chokeholds and neck restraints, requiring officers to intervene if they witness abuse, a requirement that the police chief approves any use of crowd control weapons, changes to the discipline procedures requiring timely decisions, and a mandate the city develop a plan to audit body-worn footage. The city agreed to incorporate all these changes on a permanent basis.

More changes came in 2021. MPD curbed the use of "pretextual stops" or traffic stops for minor traffic violations, prohibited officers from temporarily shutting off their body cams, redesigned its recruit application process to put more emphasis on social service experience and Minneapolis residency, added additional restrictions to the use of crowd control weapons, and updated their field training officer program to increase oversight and ongoing discipline review.

Notable changes this year include an effort by Frey and Council member Lisa Palmisano to overhaul how police records are processed, and a new program training officers on how to intervene. The most significant shift occurred in April when, in the wake of the killing of Amir Locke, the mayor introduced a more aggressive prohibition on no-knock warrants.

When asked if all of these reforms constituted the kind of "deep structural reform" of MPD that Frey called for in the wake of Floyd’s murder, Levy Armstrong was unequivocal.

"No, I don't think that he accomplished that," she said.

"I would hope for what we've been calling for, even before George Floyd was killed, which was an overhaul of the Minneapolis Police Department in terms of policy, in terms of our hiring practices, in terms of a more robust disciplinary system, and in terms of ongoing accountability and transparency," Levy Armstrong added.

With his "both/and" public safety strategy, Frey has also steadily increased funding for the city's Office of Violence Prevention and programs like Group Violence Intervention (GVI), which works to deescalate gang conflicts and connect at-risk youth to city services.

Levy Armstrong said she agrees with that approach but thinks more should be done.

"I'm glad that there has been a stronger focus on violence prevention at the same time, we still haven't seen significant levels of investment within the Black community, particularly in terms of job creation, housing stability, and investments in our young people," she said.

Community driven change

PJ Hill leads a protest for racial justice in Minneapolis following the murder of George Floyd in 2020. (Photo provided)

The community impact of the Floyd-inspired social movement didn’t just come through policy changes. Anika Bowie, an organizer with the Minneapolis NAACP, recalls how during the height of the unrest, the organization provided support for neighbors in North Minneapolis who came together to form community patrols, .

"The people who showed up were folks who really value their community and had something to defend. And As tragic and immoral as George Floyd's murder was, the community's response showed the power of people working together to solve issues," she said.

NAACP Vice President PJ Hill, a financial advisor with NorthRock Partners, organized two large rallies in the aftermath Floyd’s murder, the Take the Knee rally and the 10K March, before then pivoting to partnering with local business executives and investors who wanted to do more to support the Black community.

He has continued work in a similar vein as the co-chair of the city’s Inclusive Economic Recovery workgroup, which in March presented a slate of recommendations to the city, including strategies to support homeownership for BIPOC communities and better support for BIPOC entrepreneurs.

Now, as he waits to see how the city will implement the recommendations, he worries about how efforts like his can keep momentum.

"My hope, as I continue to do this work to help people build wealth and liberate people economically, is that people keep that sense of urgency and never forget that feeling that they felt when they watched that video for the first time of how do we make change? And that feeling dissipates. But what do you need to keep you going? To continue to try to level the playing field?" he asked.