Sitting Bull's great-grandson confirmed using DNA from lock of hair

The great-grandson of famed Lakota Sioux Chief Sitting Bull has been confirmed as his closest living descendant by scientists, who used a new technique in which ancient DNA fragments were extracted from the Native American leader's hair.

Ernie Lapointe, of South Dakota, had wished to have their familial relationship confirmed through genetic analysis to put an end to speculation and to help settle concerns over Sitting Bull’s final resting place, according to a news release.

The results of the genetic analysis were published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances. It was believed to be the first time ancient DNA has been used to confirm a familial relationship between the living and historical individuals, researchers said.

The technique searches for "autosomal DNA" in the genetic fragments. In this case, the team used DNA extracted from Sitting Bull’s hair lock, which was in poor condition after having been stored for more than a century at room temperature in the Smithsonian Museum. The hair was later returned to Lapointe and his sisters in 2007.

"Since we inherit half of our autosomal DNA from our father and half from our mother, this means genetic matches can be checked irrespective of whether an ancestor is on the father or mother’s side of the family," the researchers explained.

The DNA from the Lakota Sioux leader’s scalp lock was compared to DNA samples from Lapointe and other Lakota Sioux. The resulting match confirmed that Lapointe is, in fact, Sitting Bull’s great-grandson — and his closest living relative, the team said.

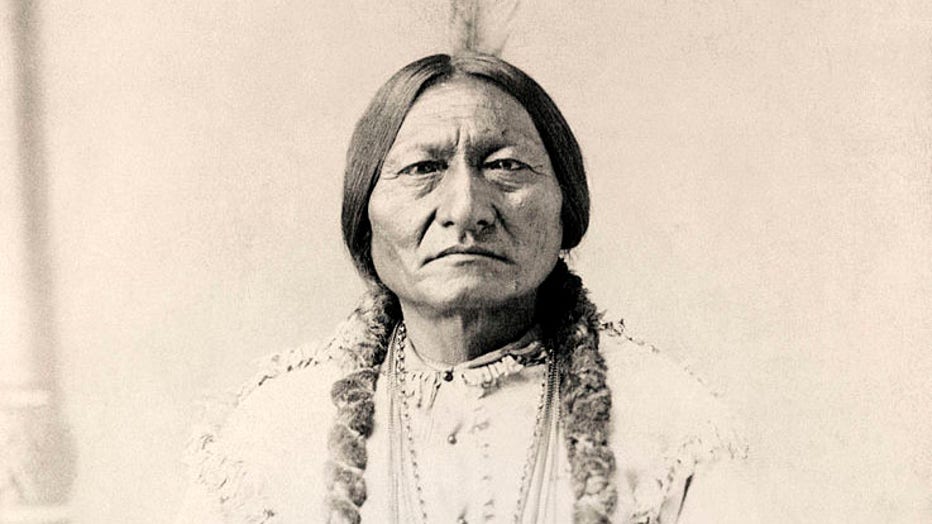

UNSPECIFIED - CIRCA 1800: Sitting Bull portrait on a 19th-century cabinet card. (Photo by Universal History Archive/Getty Images)

"Autosomal DNA is our non-gender-specific DNA. We managed to locate sufficient amounts of autosomal DNA in Sitting Bull’s hair sample, and compare it to the DNA sample from Ernie Lapointe and other Lakota Sioux – and were delighted to find that it matched," said Professor Eske Willerslev in the University of Cambridge’s Department of Zoology and Lundbeck Foundation GeoGenetics Centre. Willerslev and a team of scientists developed the new technique.

RELATED: DNA links couple to 1991 cold case of abandoned infant remains, police say

Lapointe believes that Sitting Bull’s bones currently lie at a site in Mobridge, South Dakota, in a place that has "no significant connection to Sitting Bull and the culture he represented," according to the researchers.

There are two official burial sites for Sitting Bull, one at Fort Yates, North Dakota, and in Mobridge, and both receive visitors. Lapointe also has concerns about the care of the gravesite.

With the DNA confirmation of his bloodline, Lapointe hopes to rebury the great Native American leader’s bones "in a more appropriate location."

It took the scientists 14 years to find a way of extracting useable DNA from the 5 to 6 centimeter (roughly 2 inch) piece of Sitting Bull’s hair, researchers said. The work now paves the way for similar DNA testing of the relationship between many other long-dead historical figures and their possible living descendants.

"In principle, you could investigate whoever you want – from outlaws like Jesse James to the Russian tsar’s family, the Romanovs," Willerslev said. "If there is access to old DNA – typically extracted from bones, hair or teeth, they can be examined in the same way."

Who was Sitting Bull?

Sitting Bull, the Native American leader and military leader also known as Tatanka-Iyotanka, lived from 1831 to 1890. He is best known for having united the Sioux tribes of the American Great Plains against White settlers taking their tribal land, according to History.com.

During the 1876 Battle of Little Bighorn, also known as the "Battle of the Greasy Grass," Sitting Bull helped lead united tribes to victory against U.S. General George Armstrong Custer.

"The blood-soaked feat... will forever symbolize the resistance of Native Americans to the white man’s insatiable appetite for empire-building," the news release stated.

Sitting Bull was later assassinated in 1890 by the "Indian Police," acting on behalf of the U.S. government, on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation.

Willerslev said Sitting Bull had always been his hero, "ever since I was a boy."

"I admire his courage and his drive. That’s why I almost choked on my coffee when I read in a magazine in 2007 that the Smithsonian Museum had decided to return Sitting Bull’s hair to Ernie Lapointe and his three sisters, in accordance with new US legislation on the repatriation of museum objects," Willerslev said in the news release.

Willerslev said he later wrote to Lapointe and explained that he specialized in the analysis of ancient DNA, asking if he could do the new technique on the Native American leader’s hair — referring to it as "a great honour."

This story was reported from Cincinnati.