With EPA's rollback of wetland protections, Michigan officials say we're setting "a dangerous precedent"

(FOX 2) - First, there was the Bush rule, then the Obama rule, then finally the Trump rule.

That’s how Todd Losee, the former president of the Michigan Wetlands Association describes the series of protections that our country’s marshes and swamps have enjoyed in the past decades.

“Since the decision in the early 2000’s by the federal supreme court, jurisdiction has been a total mess,” he said.

That was the Bush rule, which stated wetlands have a “significant nexus” and carry some kind of function to be protected. However, defining wetland function proved very confusing. During Obama’s term, his EPA sought to better define which wetlands were protected, and subsequently expanded federal jurisdiction over many of them in 2015.

Then on Sept. 12, the current head of the Environmental Protection Agency co-authored an opinion piece in the Des Moines Register, outlining the Trump rule.

“Today, EPA and the Department of the Army will finalize a rule to repeal the previous administration’s overreach in the federal regulation of waters and wetlands,” wrote EPA Head Andrew Wheeler and Army Assistant Secretary R.D. James.

The two said the new proposal offers a “more precise definition” and would mean “farmers, land owners and businesses will spend less time and money” deciding if they needed a permit to develop that land, and instead could expending more money on upgrading infrastructure and growing food.

While this new definition made headlines the day it was published, it wasn’t much of a surprise. President Trump issued an executive order during the early days of his tenure in 2017 that instructed federal agencies to work on repealing the 2015 rule. What might be a surprise is how little this move affects Michigan.

However, officials say that really isn’t the point.

“Michigan’s in a bit of a different position because we have a fairly strong state run program related to wetlands and protections for them,” said Tom Ziminicki, the agriculture policy director with the Michigan Environmental Council. “With a change in the clean water rule, the feds are saying they shouldn’t have oversight over this. That states should basically assume control of water.”

Michigan is one of two states in the country with outlined protections of its wetlands, the other being New Jersey. Michigan’s Wetlands Protection allocates $2 million a year from the state’s budget to regulate filling, dredging and draining its marshes and swamps. For any wetlands under state protection, any farmer, developer or homeowner that wants to modify that land must apply for a permit from the state to do so. The statute has been in place since 1979.

This isn’t a popular rule among the state’s farmers and a collection of its legislators, who have attempted to role back those protections many times in recent years - the most recent being during the 2018 lame duck period after the midterm elections.

The Michigan Farm Bureau claims the protections have stymied farmers from making a profit on their land.

“EPA's announcement repealing the 2015 rule that expanded the definition of what could be regulated as a Water of the United States (WOTUS) came as a great relief to farmers across Michigan and the country,” said Carl Bednarski, the farm bureau president in a statement. “Farmers depend on and support protecting clean water. However, the 2015 WOTUS rule was simply unrealistic and a case of regulatory over-reach. It would have regulated wet spots in farm fields, features created by storm-water, and areas of land that are dry most of the year.”

Opponents of the 2015 bill said the Obama administration’s increased protections was federal overreach and not the original intention of the Clean Water Act, which was to regulate “navigable waters” used in interstate commerce and the tributaries that flow into them. Any more regulation should be left up to the state.

Ziminicki said the move by Wheeler and the EPA is not surprising, but “a really short-sighted move.”

“It’s hilarious when Trump talks about how he loves more crystal clean water. It’s hilarious when he talks about that and his administration makes these changes,” he said. “Wetlands in particular are one of the most cost-efficient ways to deal with flooding issues and deal with climate change and nutrient and pollutant concerns.”

Wetlands do provide an amalgamation of services to the surrounding ecology and are considered a key resource due to its natural filtration capabilities. They stave off erosion, provide habitat for insects, birds and other animals and filter out harmful contaminants and pollutants released by industry. And as Ziminicki states, they are effective at mitigating floods - a problem Detroit often struggles with.

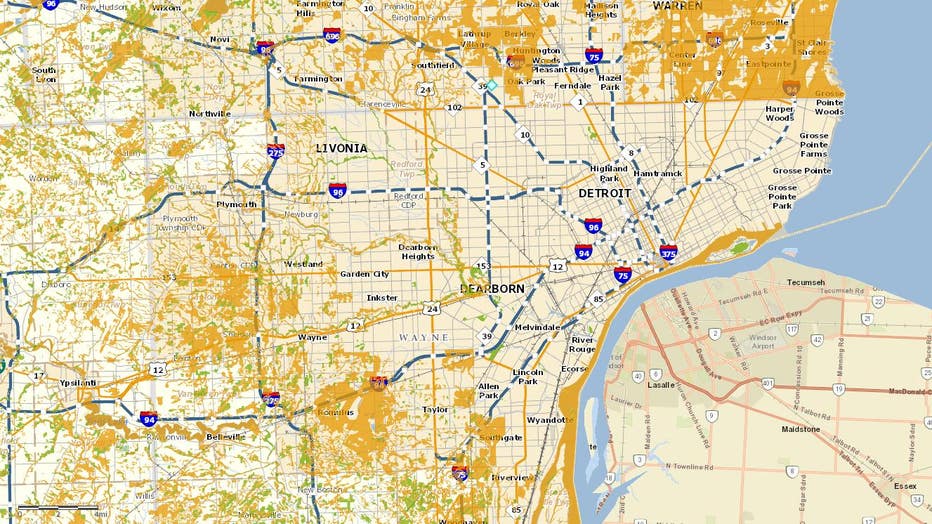

Sections of the map in yellow represent wetlands

Southeast Michigan used to be blanketed with wetlands. Despite the area having lost between 80 to 90 percent of its wetlands, the area still has plenty around the region. Officials attribute much of what is still in place a result of the state’s protections of wetlands.

“If we didn’t have this law, there’s no doubt you would not have wetlands,” said Losee.

That’s why roads in subdivisions of metro cities have curvy roads - they were designed to work in conjunction with wetlands, instead of just removing them entirely. What Ziminicki said people often forget are wetlands are puzzle pieces in a system that’s all connected. No where is that more true than in the Great Lakes. But Michigan stands alone among Great Lakes states in its protections, and if other states don’t offer the same regulations it can disrupt the whole system.

“If we don’t have strong standards that all states are having to meet by the feds, then we’re rely on states to step up to protect water in their state that eventually makes it into the basin,” he said. “We’re seeing a dangerous precedent for what we want water quality to look like moving forward.”

By politicizing clean water and standards for clean water, it could increase conflicts over how the resource gets used.