Highly contagious: Michigan officials explain why measles cases at 28-year high

(FOX 2) - Like a cruel joke, Michigan's measles predicament was almost foretold less than a year ago.

Authors of a 2018 study out of the Baylor College of Medicine said states with a high number of non-medical exemptions for vaccines might mean more cases in those states. The evidence “suggests that outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases could either originate from or spread rapidly throughout these populations of un-immunized, unprotected children.”

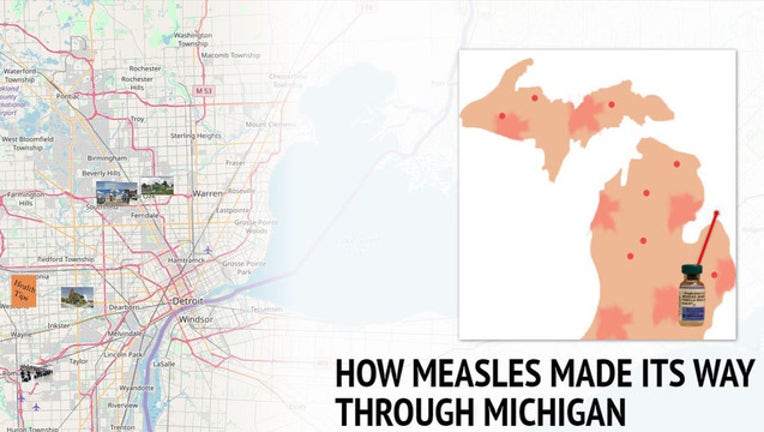

One of those locations was the Detroit area - specifically Oakland, Macomb and Wayne counties.

A year later, that same region is under threat of the state's largest measles outbreak in almost 30 years. With 40 reported cases since mid-March, experts are warning if the outbreak is not curbed soon the infection rate may continue to accelerate.

“I think it's something parents should be concerned about,” said Paul Kilgore at the Eugene Applebaum College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences at Wayne State. “The most important intervention they can do is to actually get vaccinated. If nothing else is done, it will continue to be spread.”

Measles is one of the most infectious diseases out there, capable of spreading from one case to 18 people.

“The number of people that an infected person can spread (the disease) to is very high. It's one of the highest that we know of,” said Kilgore.

Part of the reason it's so contagious is the disease's ability to travel on airborne droplets; anytime someone that's infected coughs or sneezes, the disease can go airborne.

Symptoms also don't show up immediately upon infection. Someone who has contracted the disease may not know about the infection for days, more than enough time for them to reemerge in public and spread the disease further. Symptoms like rashes, high fevers and coughs can turn to diarrhea and vomiting - which, in turn, can dehydrate those without enough reserves of water.

However, measles is also moving with more efficiency because of the large number of unvaccinated people.

“The reason why measles has been making its way so quickly through Oakland County is because a large number of children are unvaccinated and parents are asking for non-medical exemptions to vaccination requirements in school,” wrote Abram Wagner, an assistant professor at the University of Michigan in an email.

In a National Center for Biotechnology Information study, Wagner said the national average for exemptions “hovered around 2 percent.” Oakland County's exemption rate is 4.8 percent. Wagner points to Michigan's status as one of 17 states that allows for philosophical exemptions to vaccinations.

“And I realize that 5 percent doesn't seem like a lot, but when measles is so infectious, and certain schools likely have very high exemption rates, this offers an in for the virus,” said Wagner.

As the outbreak has progressed, indeed it has been children that are being diagnosed with measles. However, state health officials noted the people who first contracted the disease in March were actually adults. That's not what happened the last time so many people in Michigan were exposed to measles.

“It's quite a bit different than in the 90s. We're not seeing the cases in this outbreak that were in the previous one” said Bob Swanson, the immunization program director. “I worked that outbreak. That primarily hit young children. This has been more on adults.”

Back then, states recommended only one measles vaccination for young kids. That was rendered 95 percent effective, which led to occasional “break-through cases” where some who were vaccinated still contracted the disease. Now two MMR vaccines are recommended, which carries a protection rate closer to 97 or 98 percent.

While adults are recommended to only receive one dose, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention leaves the option open to anybody interested in a second dose. The best advice offered by the MDHHS is to consult one's healthcare provider.

As the outbreak has spread, the state health department has used a multi-pronged approach to push back against the outbreak. Every day, the MDHHS hosts a conference call with counties that already have cases of measles or are near those counties. Along with updating county health officials on investigations into potential exposure sites, the department is also offering advice on answering media questions about the outbreak and making sure every county is stocked with vaccines.

“Everybody that has worked in the local health departments are boots on the ground,” said Lynn Sutfin, spokeswoman for the MDHHS. “What all of them have done has reached out to schools and day cares, giving them information on the outbreak...and info to help get parents vaccinated.”

Some school districts are taking more extreme approaches to the outbreak. In early April, Derby Middle School in Birmingham said it was requiring any students who are not vaccinated to stay home from the school for 21 days following a confirmed case. School officials stated they were following Oakland County Health Department guidelines by excluding any children who haven't been vaccinated or are under vaccinated.

Sutfin said Oakland County, the epicenter of the outbreak, has done a good job by hosting vaccination clinics - which seems to be paying off. A recent count of administered MMR vaccinations over the last couple weeks now totals around 2,000. There's also been a recent lull in the number of individuals being diagnosed with measles.

“The last few days have been a bit slower,” Swanson said. “We're hoping that's attributable to the number of vaccines that have been administered.”

There were 30 cases identified by April 1. Since then, only 10 cases have been confirmed. Swanson said 21 cases were identified in the first wave of diagnoses. As more cases are diagnosed, it gets harder to track each wave because while it can take 14 days for symptoms to show up, that's not always the case. That also makes it difficult to pinpoint where in the outbreak Michigan finds itself.

“In the beginning of an outbreak, you tend to see low numbers,” he said. “As the outbreak proceeds, depending on what you do, you'll see an uptick in cases. That trajectory is key because the speed of the spread gives you an indicator of what will happen next.”

And what happens next is hard to predict. As Swanson mentioned the number of cases being discovered isn't as large as it used to be - which is good news. But with outbreaks occurring in other states, there's potential for anything to happen.

“Unfortunately this outbreak could blow up larger - like it has in Washington State or New York City,” Wagner wrote, “and the absolute worst case scenario is if there was such a breakdown in vaccination coverage that virus was able to spread for over a year within the country - which would mean that measles is no longer eliminated in the United States and it is once more an endemic disease.”