Inside the forensic labs cracking Michigan cold cases

New technology brings new hope to decades-old cold cases in Michigan

It's the inner workings of crime labs like Michigan State Police's facility in Northville that are bringing new light to old cases. There is a cycle of new technology that comes out periodically that enables police to solve some of the trickiest puzzles. Investigators hope that progress will help them put some cases to bed.

NORTHVILLE, Mich. (FOX 2) - A single forensic laboratory can process thousands of pieces of evidence a year.

It could be a blood stain or a hair strand. Each sliver of evidence represents a victim or a suspect - the genetic footprint that could be the key to cracking some of the toughest cases that have stymied investigators for decades.

That includes the death of Bertha Warren, the 47-year-old Romulus woman who was last seen by her daughter. After disappearing on Aug. 16, 1981, her body was discovered dumped in the woods in Sumpter Township.

She was found by two men who were hunting birds at the time.

"One of them, because they didn't have a cellphone, one of them started walking down the road to someone's house to call police," said Sgt. Les Rochefort to put the era into context, "and the other stayed at the road."

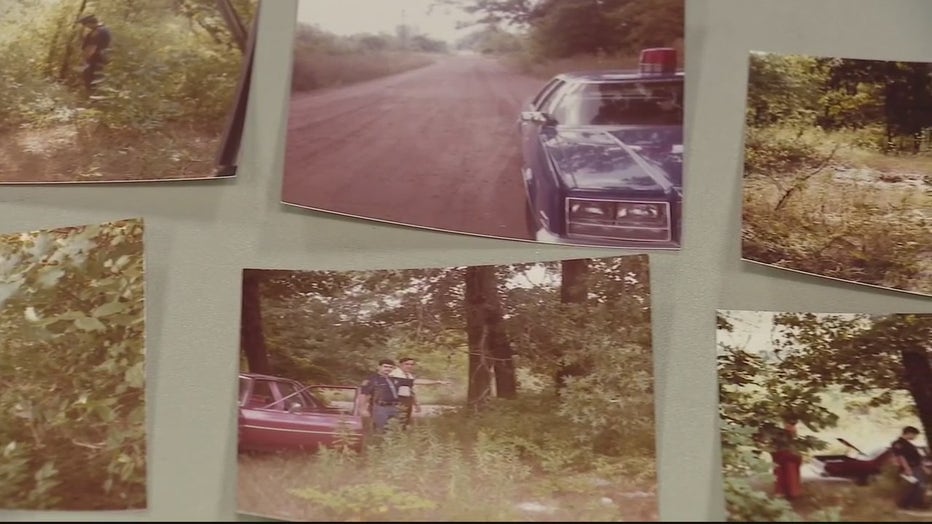

The crime scene images show a different era. With boxier cars and sepia tone filters on the photographs.

Some of the images from the crime scene in Sumpter Township where Bertha Warren's body was found.

Investigators believe Warren was murdered somewhere else before her body was brought to the forest.

It's into this murky world of still-undiscovered clues that diligent crime technicians and hopeful detectives on cold case units dive in every day. That includes Rochfort, who says he has a mind for the cases brought before him.

"I like putting together puzzles and these are some of the greatest puzzles," he said.

MORE: Cargo containing gold worth nearly $15M stolen from Toronto airport

Rochfort has returned to the murder of Warren in hopes of uncovering a new piece of the case that could lead to a suspect - or at least closure for the family that may have given up on solving the case.

But doing that requires looking at evidence that police at the time likely had no idea would be helpful.

"They probably didn't even realize what they were collecting would be DNA. They were probably thought 'I'm gonna swab a blood stain on a hand to test the blood and try to identify the blood type' not knowing in the future we could test the blood to see whose it may be," said Kate Maggert, a forensic scientist.

Maggert operates out of a lab like the one located in Northville, where an intersection of science and history converge.

There are eight labs in Michigan that carefully analyze evidence collected from crime scene that could be hours old - or decades old. That includes Warren's case, where DNA from pieces of clothing are being tested for anything helpful.

MORE: 4 women charged with stealing over $4,000 in Lululemon clothing from Birmingham store

With any luck, just a small amount of evidence can be enough to make an arrest.

"DNA processing and forensic DNA changes almost annually." said Brandon Good, the lab manager.

"There is always a new and better way to do something so its very common that every four or five years detectives will come to us with cold cases they have been working on and will want to sit down with a supervisor or a scientist to go over their case to see with this new technology is there something that we can do."

The Northville lab tests an estimated 6,000 samples a year. Some come with closure, while others with their own horrific past. But when they help lead to progress, it can be the greatest feeling in the world, Maggert says.

"You get to see some of the details of what happened in these cases, and it's horrific. So just to be able to provide some information that assists in that case is rewarding and that has happened more often than I can count," she said.