Great Lakes expected to break records in 2020 as Michigan cities struggle to prepare

ST. CLAIR SHORES, Mich. - When Nikki and Kim Grodus were eyeing a home they wanted to buy in St. Clair Shores, they were skeptical about the water creeping up the side of the house. To them, it looked high. To their eventual neighbors, they had nothing to worry about.

“I was like ‘I don’t know, it looks a little iffy,’” Nikki said, “and everyone was like ‘it’s as high as it’s ever been, it’s not going any higher.’”

But the home was on one of the city’s canals and had a unique vibe they were after. So they bought it. That was in June 2018.

The Grodus’ home has an unusual feature compared to its neighboring houses in that no buffer exists between the foundation and the canal. Only a wall separates their basement from the water. It even features windows that open where people can look through and see the water.

“Unfortunately, our wall is our sea wall - the wall of the house. We’re really the only ones that can be compromised structurally,” Kim said. “We ended up looking and seeing ‘it’s getting higher, it’s getting higher.’”

Even as well-informed neighbors told them they didn’t have anything to worry about, the water continued to rise. An exceptionally wet fall and majority ice cover over the winter in 2018-19 gave way to growing concerns from Nikki and Kim their home would be at the mercy of mother nature.

To keep out the water, Nikki waterproofed the windows shut as a sump pump from the basement ran constantly, removing flooded water back out into the canal. The couple filled sandbags and rested them against the window to absorb anything else coming through.

Water still managed to breach the house. Not just through the basement wall bordering the canal, but via the side of the house as well. The drains that bordered the Grodus’ house from their neighbors overflowed, flooding the sidewalk and spilling through the door, eventually cascading into the basement from a separate side.

“Everybody reassured us that it wouldn’t happen, and even if it did, even if it crested above the ledge, it couldn’t go through the glass,” Nikki said. “I had five to six inches before it became a threat. Then it went all the way above this window.”

Nikki Grodus points to the side of her home where lake levels rose to in 2019. Her home is unique because the basement wall is all that stands between the canal and the home's foundation.

Despite the unorthodox foundation of the Grodus’ house, a similar story was told all across Michigan’s coastline in 2019: Homes inundated with flooding, marinas underwater and main roads impassable. And if Army Corps of Engineers projections remain consistent, 2020 will bring more of the same.

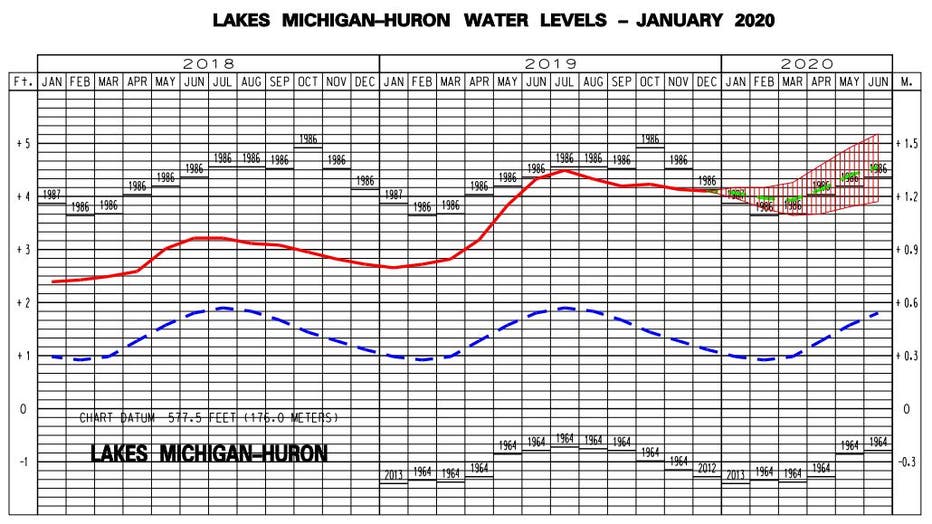

“Right now, what we’re seeing is a 50-50 shot the lake levels in Michigan and Huron will break their record high - those are pretty good odds that it is going to happen, so asking if we’re prepared is a good question,” said Joel Brammeier, CEO of the Alliance for Great Lakes. “I don’t think any community is truly prepared as it could be.”

RELATED: Great Lakes water levels could be even higher in 2020

Since lake levels reached record lows a decade ago, the Great Lakes have rebounded in an unprecedented way. In 2019, Lakes Superior, Erie, Ontario, and Lake St. Clair all broke record highs, and Lakes Michigan and Huron almost did. Years of heavy precipitation during the region’s warmer seasons and above-average ice cover preventing evaporation in the winter have coalesced in lake levels that flood indiscriminately across the state.

The fluctuations in the lake levels have made it almost impossible for city managers to plan accordingly. Cities can pay more to raise their sea walls if they expect lake levels to rise, but if the opposite happens and the lakes decline, it could mean an expensive project that protects against a threat that’s no longer present.

“No government can control mother nature,” said Pete Dame, city manager of Grosse Pointe. “You don’t know how high the levels of the lake are going to be. It could go into the yards - or if we have a mild winter, if the ice doesn’t cover 90 percent of the Great Lakes...that’s the scenario where if we don't have the same weather patterns that created this pattern, then you spend $250,000 to raise roads - fixing a problem that doesn't exist anymore.”

Grosse Pointe spent $70,000 to protect its marina from the rising waters in 2019. Four of the communities’ cul-de-sacs that sit on Lake St. Clair’s coast were flooded prior to any heavy rain event. No homes were damaged, but residents drove through 10 inches of water just to get to their driveway. The seawall bordering Lake Front Park, the lowest point of elevation in the area, didn’t keep water out. Instead, the city had to use sandbags

RELATED: Wetter than most: It's rained 23 out of 31 days in May

Dame said if the water had gotten much higher, the city would have had to shut down the marina entirely to avoid electrical conduits underneath the docks from creating more problems. All in all, the city shelled out $100,000 that wasn’t budgeted to mitigate the damage.

“I’ve been hearing about this issue for years, but it’s rather shocking to get out of the car and see how bad the erosion is and how close it is to the Lake Shore Drive,” added Dame, who went on a tour of flooded areas in 2019.

St. Clair Shores City Manager Matthew Coppler said the last time flooding here was so extreme was in 1986, when most of the Great Lakes set record-high lake levels. Last year served as a reminder for residents of what happens when water does get high and believes it will also be used as an educational tool that municipalities and residents can plan for in the future.

“...there was a lot of opportunity for learning,” Coppler said. “(It) raised the issue more to a forefront because I think what you see, since it’s been a while since they (lake levels) were so high, there are new residents in those houses. People forget in the mid-80s it was this bad.”

“A lot of people have forgotten, now they’ve been reminded,” he added.

RELATED: St. Clair County on edge as waters rise during flood warning

St. Clair Shores has been working to improve its stormwater management, making sure its pumps are working and possibly adding an additional pump station where officials anticipate flooding to be an issue. The city is also adding additional sandbags to keep the lake out.

South of Detroit in Monroe County where flooding is more frequent and more extreme, county commissioners took proactive measures a year ago when their drain commissioner lobbied for new pumps. The $250,000 purchase replaced their antiquated gas pumps - and they arrived just in time.

“The biggest use for the pumps is flooding on coastal areas. They arrived the day before we had our first flood event,” said David Thompson, county drain commissioner for Monroe. “Nice thing about these new pumps, we’re able to pump one community dry a day-and-a-half earlier. The damage is done, but the sooner you can dry them out, the more you can save.”

Thompson emphasizes he has no control over the lake levels or the flooding they cause. He also has no jurisdiction over the dikes that are meant to prevent flooding - most of which are privately owned. However, when high water events occur, the pumps can be transported to areas hardest hit to avoid more damage.

Sometimes though, even the pumps aren’t enough.

“At one point, we had 21,000 gallons of water per minute pumping, and we were still losing a foot an hour,” Thompson said. “At the end of the day, mother nature wins.”

Lake level forecasting from the Army Corps of Engineers only extends six months into the future, but the numbers predicted are enough to worry residents around the state. While Lakes Michigan and Huron appear most likely to set new record highs in the summer, it’s within the realm of possibility that each lake could set a new record.

The lake levels at the end of 2019 were so high, that even if the Great Lakes region has its driest period ever recorded, lake levels will still be above average in almost every lake, beside Lake Ontario.

After surpassing record water levels in 2019, Lake St. Clair is expected to reach similar heights in 2020. The red line represents measured lake heights in past years. The blue line represents the average recorded heights of the lake over time. The g (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers)

Increasingly aware of these predictions and what it means for the cities at the mercy of the lakes, the Michigan Municipal League (MML) has started creating more noise at the legislature last June, emphasizing the need for more spending on flood mitigation and raising awareness about the potential for more damage.

“These are conversations we’re starting to have. It’s something that we need to address,” said Herasanna Richards, a legislative associate at the MML. “What is a way that we can do this that won’t cause significant financial distress for these communities? You have to repair a sinkhole or a bridge, but this is causing more damage than just houses being washed away. The problem is widespread and the longer we don’t do anything, the cost will compound.”

Working in conjunction with the MML is Rep. Joe Tate (D-Grosse Pointe), whose district was one of the hardest hit on the state’s east coast last year. Last December, he went on a water tour with several city managers like Dame of Grosse Pointe and Shane Reeside of Grosse Pointe Farms, looking at where there was evidence of flood damage months after high water events.

“(The damage) in my neighborhood in Jefferson Chalmers - that really got the ball rolling. It’s one thing to hear about it, but it’s another thing to drive down the neighborhood and see sandbags holding back the Detroit River,” Tate said. “We’re starting to have that conversation, but there’s going to have to be a comprehensive plan around this.”

Tate believes solutions won’t just happen at the local or state level but through collaboration between all levels of government - including regional and international.

After the year’s first major rainfall that soaked Detroit and flooded major highways in early May, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer declared a state of emergency for the Wayne County. That unlocked funds communities could use to repair damages. Last December, 10 state legislators from districts hit by high lake levels requested Whitmer do the same thing in an effort to offer some relief.

Unfortunately, because emergency declarations are only approved following catastrophic events and not damage sustained over a period of time, county executives can’t apply for those funds. The MML is considering working to rewrite that language to give counties more flexibility in applying for funds.

To alleviate some of the pain, the Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy (EGLE) sped up the time it takes to get a sea wall permit approved, turning one around within days, instead of three months. Since then the number of permits approved has skyrocketed from 264 in 2014 to 836 in 2019.

In the first quarter of the 2020 fiscal year, EGLE had received 452 permits for seawalls and revetments and other shoreline protection measures. Their spokesperson estimates if that rate holds up, they are on track to receive more than 1,800 applications this time around - more than double that of 2019.

As high water levels threatened her basement wall, Nikki Grodus was also had to worry about encroaching water from the sides as well. Along with her wife Kim, the two bagged sandbags in hopes of keeping out water.

Nikki and Kim Grodus might very well be one of those households that applies for a permit in the coming months. On Dec. 26, Nikki posted in a St. Clair Shores Resident Facebook group looking for help - seeking advice on what options were available. Some people said to build a sea wall, others told her to raise the house or empty the basement. A few cheeky comments told her she should just move.

“Telling me to move doesn’t help, guys. Please, this is serious and I just moved here. I can’t move out,” she later commented.

Instead, she’s planning on having a couple of seawall companies give her a quote. She’s also considering spreading liquid rubber on the side of the house then layering a tough plastic material on top, which would create a waterproof skirt to buffer the house.

But if the water rises only a little higher than it did last year, the basement will be completely underwater and will then be touching the home’s first-floor wood paneling.

“At seven to 10 inches higher, we go from brick and mortar to wood and paper.”

Jack Nissen is a reporter at FOX 2 Detroit. You can contact him at (248) 552-5269 or at Jack.Nissen@Foxtv.com