Life after COVID-19 won't be normal for Michigan workers as manufacturing needs system overhaul

DETROIT - When autoworkers go back to work, they’ll likely find their day a little different.

There’s the two and three-man jobs needed for putting the vehicle together. Some of the equipment requires multiple pairs of hands to operate. One worker in the body shop estimates their two-man jobs put them about seven feet apart during some of the heavier lifting.

Then there are the breakfast and lunch lulls in the break rooms that won’t be attended by entire teams of plant workers. The communal microwaves, refrigerators, provision cabinets, and coffee makers might not be open for use. Access to the terminal to see payroll updates will have to be limited.

“There are occasions when someone has spat on the floor inside of the building. There's times we are working so close that we can actually smell the coffee on someone’s breath,” said one UAW worker. “Some workers have poor hygiene. Others leave soiled gloves and remnants like candy wrappers lying around.”

The UAW employee, who asked they not be identified, is among the thousands that staff the Michigan Assembly Plant in Wayne where they're been building the Ford Ranger. Shift rotations might have to go longer to reduce the number of workers occupying one area or one machine.

Even the team leaders that workers call when they need a break will need to find another form of communication.

“How can you remotely let somebody go pee? How can you do that? There’s no way,” said the worker.

Ford, General Motors, Fiat-Chrysler, and most other manufacturers in Michigan might soon be asking themselves the same question, among others. How can factory workers assemble a product and adhere to social distancing and safety guidelines when part of the assembly requires breaking those rules?

The solution, Tom Kelly of Automation Alley says, will come “in a million different ways at a million different companies.”

“It is going to be very painful to go through this process. It’s easy to shut down the economy, but much harder to restart the economy,” he said. “The plane is going down. The question is when does someone ask when we restart the engines.”

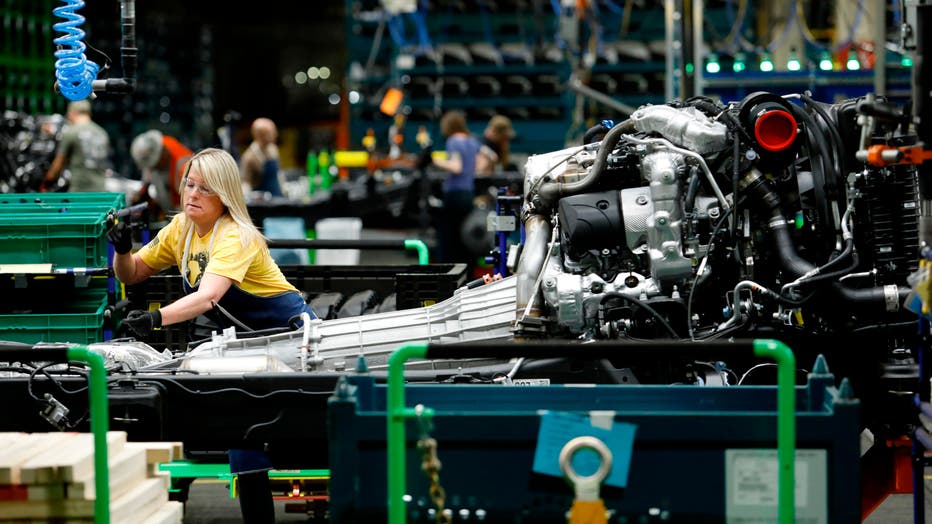

Line workers work on the chassis of full-size General Motors pickup trucks at the Flint Assembly plant on June 12, 2019 in Flint, Michigan. - GM announced the second major expansion of its full-size pickup production capacity this year: with a $150 m

It’s anyone’s guess when Michigan’s economic engine gets turned back on. But the longer it takes, the worse the state’s outlook will be. At 24%, Michigan’s jobless rate is among the highest in the country.

Part of that is due to manufacturing’s role in the state’s economy. Employing more than 628,700 workers in the state, manufacturing accounts for 20.5% of non-governmental GDP. Kelly says that’s almost double the national average.

One reason the manufacturing sector was hit so hard is because of its integration into the global supply chain. When production stopped in China and Europe, the effects were felt everywhere - especially in Michigan. Manufacturing also can’t be work that’s done from home. Employees that operate the assembly line can’t do so remotely. And without proper safety protocols in place, those same employees won’t be permitted to come to work.

“The challenge is we’re a manufacturing town,” said David Yanez, founder, and CEO of Andonix, a software company out of Detroit that’s leading the transition for some companies. “Our playbooks weren’t prepared for a pandemic. So it will change work habits and behaviors.”

Not every manufacturing plant has been shuttered. Some, like GM’s Warren Plant that’s making face masks or Ford’s Rawsonville Components Plant in Ypsilanti that’s building ventilators, have been deemed essential.

RELATED: GM, Ford making plans for safe return to plants

But for much of the manufacturing sector, experts anticipate when the industry reopens, it will start small.

“It really is small goes to medium goes to large. In the general sense, smaller businesses - they can be a little faster because they are smaller,” said John Walsh, president, and CEO of the Michigan Manufacturers Association (MMA). “If you’re much larger, you have to order all your PPE supplies, probably hire a third party company to do cleaning.”

“The problem is they (larger manufacturers) have a scaling problem. They’re so big, so many people and so many supply chains that have to be stitched together,” Kelly said. “The supply chain has to start small and ramp-up to the bigs.”

The whole process will likely take several weeks, says Jim Cain, a spokesman for GM.

“In North America, we have dozens of suppliers in dozens of states as well as Canada and Mexico that all have to be ready to go,” he said. “With proper safety procedures in place and employees ready to go back and our own supply chains primed, we’ll move through this process of suppliers restarting, then component plants, then assembly plants.”

Many of the safety procedures GM will mimic are those used in plants already building essential products and factories up and running in China.

Behind the scenes at GM’s factory where volunteers produce thousands of face masks daily

FOX 2's Erika Erickson takes us to the GM Tech Center in Warren, where volunteers are working 10-hour shifts to produce thousands of face masks a day.

For the facilities that invested in automation and digitized part of their work, Kelly said they’ll have an easier time weathering the storm. It could be grocery stores with online order options that limit face-to-face interaction or factories automating more of the two-person jobs. Even the people making face masks in their garage with 3-D printers are proving global pandemics can’t stop everything.

Despite the innovation, the MMA estimates more than half of the state’s businesses have ceased production. When employees do return to work, companies need to focus on one goal over the next several weeks: survive.

“Nothing is going to change other than survival. ‘I need cash in my business. That is the oxygen I need to survive,’” Kelly said. “In the short term, it’s anything goes, anything you need to do. You can’t focus on watching the rainbow if your boat is sinking.”

Yanez also recommended abiding by three principles aimed at curbing the spread of COVID-19; focusing on detection, prevention, and tracing. Tactics like those are already being used in cities like Detroit with essential workers like law enforcement and bus drivers. But the solutions can’t stop there.

“You have to upgrade your playbook. Think about the food industry - how effective their containment to make sure pathogens don’t mix with food,” he said. “Companies could upgrade their operations to be more like them.”

RELATED: Boy makes PPE with 3D printer, delivers them on his 13th birthday to Beaumont

Many of these steps will be engaged over the next several weeks. Michigan Gov. Whitmer has already indicated she intends to start loosening more restrictions on business in May. Ford and General Motors have also begun recalling workers to act as skeleton crews in factories as they ready for a new normal.

Hoping to guide that new normal is Rep. Haley Stevens (D-Rochester Hills), who has proposed legislation that would establish a task force of relevant agencies like the CDC and FDA that would help guide implementing safe and healthy standards for the workplace.

“This (COVID-19) is something we’re learning new things about regularly,” Stevens said. “The interagency taskforce would provide real-time guidance as we’re learning more about it.”

It’s unclear when federal guidance would come as legislation doesn’t move as quickly through the government as COVID-19 has. Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan has released the city’s own workplace standards after food marts and funeral and nursing homes requested more direction in protecting their employees. Both Andonix and LEAR have released guidebooks for how businesses can approach safety standards as well.

RELATED: General services, including lawn care, first Detroit city employees to return to work

As for the long-term implications of COVID-19’s rewiring of Michigan’s manufacturing, Kelly offered a bold prediction that other experts are beginning to echo. After decades of seeing manufacturing jobs disappear, they would begin returning stateside.

“In the past, we outsourced a lot of production mainly to China because we needed to be efficient. Why would we want to do the messy dirty stuff when we can just ship it overseas,” he said. “We are built on efficiency. But we aren’t resilient.”

The coronavirus exposed how delicate Michigan’s supply chain is. Even with a larger manufacturing presence in the state next to the rest of the country, when links in the chain broke, it broke the economy. With negative dollar signs next to the company’s preference for efficiency over resiliency, Kelly estimates a resettling of global manufacturing will take place over the next decade.

And that could have massive implications for Southeast Michigan.

"For my entire lifetime, it’s always been ‘gotta get manufacturing anywhere but America.’ That was the mantra. I think what you’re seeing is the bottom of that and now the beginning of a rise of redistribution back around the world."

Jack Nissen is a reporter at FOX 2 Detroit. You can contact him at (248) 552-5269 or at Jack.Nissen@foxtv.com